Circularity in Practice

While we recognize a circle when we see it, most people know less about how circularity works in practice as a business model. This understanding is crucial if the Norwegian economy is to go from being 2.4% circular, to as much as 20 times this figure.

is about narrowing down, slowing down and closing the use of resources.

By narrowing down, we ensure that we use less virgin materials, without this reducing the value of what we make.

By slowing down, we extend the lifetime, whether of a service, product or another essential element of a value chain.

When closing the use of resources, it is possible to renew the materials to complete a new, full-fledged round in the value chain rather than them disappearing and either being downgraded or becoming waste.

In other words, circularity is the answer to several of the world's biggest challenges. More specifically, those that revolve around scarcity of resources, depletion of ecosystems and waste.

Reality Check

235 million tons of materials–metals, fossil fuels, biomass and minerals–currently feed our annual societal needs.

97.6% of these never return to the value chain for which they were extracted, and thus neither to our economy.

Despite the number's dark nature, it also represents opportunity. According to the Circularity Gap Report, with the right priorities, restructuring and investments, we can for example cut Norway’s carbon footprint by 63%, which should result in a 45.8% circular economy. And that’s based on present conditions.

The Circularity Hierarchy

So: where to start if we are to become 45.8% circular in a short amount of time?

As of today, the linear economy rules. Within it governs a "take-use-dispose" model that took many a nation out of economic crisis in the 70s, including Norway. It is therefore, understandably, difficult for many to imagine the new system for design, production and use that circularity is.

Sure, we must radically change the way we design and operate all businesses in a circular world, which should be our collective aspiration level. The motivation? Such a scenario will still satisfy needs, but with far less strain on the planet and the environment around us.

As individuals, we are also part of the system. We have to make a change ourselves. From, for example, “use and dispose” to a "repair first" mentality.

A bigger change must be made by producers of goods and services. For example from "product as a good" to "product as a service".

From an authority perspective, both companies and people need to be incentivized, through convenience and profitability, to choose circular rather than non-circular.

We must also reward those models that ensure resource value to the greatest extent possible.

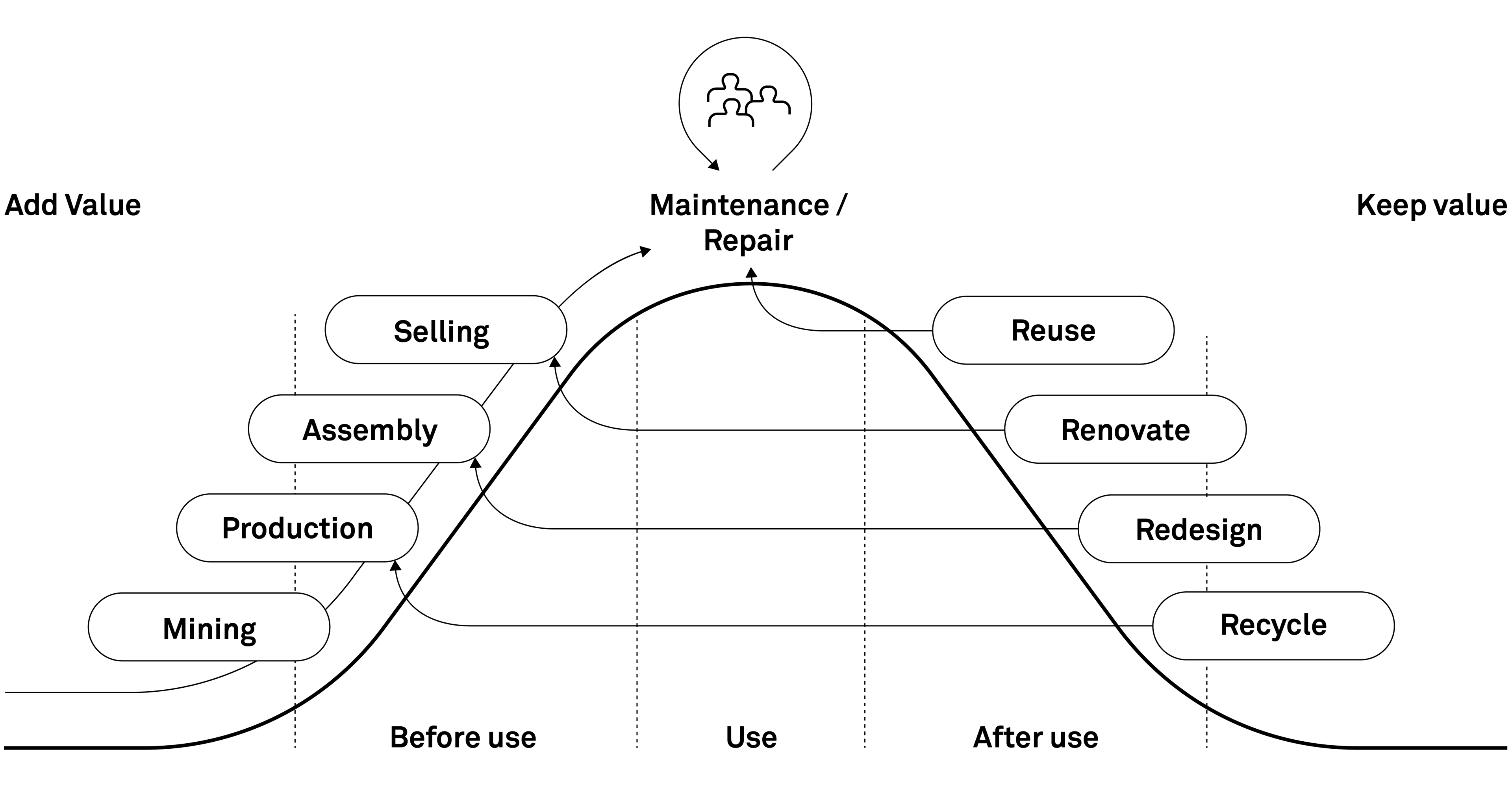

See, there are several levels of circularity, or put differently: there are several levels of how to recover the actual value of a value chain.

This resource hierarchy model builds on the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Circular Economy Systems Diagram (February, 2019)

Recycling works for certain value chains. Typically those who purify one material, so carefully produced and returned that it can be recycled. Like aluminum soda cans, household glass or metal-ware, or plastic drinking bottles.

Norsk Gjenvinning, Norway’s leading waste management provider, has developed a well-functioning system for resource sorting and consequently recycling, enabling recycling in most Norwegian homes.

However, over-extracting our resources cannot be solved with recycling alone.

Recycling is, in fact, at the bottom of the resource hierarchy shown above. The hierarchy shows the different levels one can retain value in one's own value chain (rather than losing it, which is the case for the linear model). Above recycling we find redesign, renovation or repair, and reuse. With each level comes some clear prerequisites.

Redesign requires you working with a type of material that can be transformed without causing further greater strain on the environment. Certain materials, for example, release toxins during processing, in addition to the fact that the process itself is energy intensive. We must therefore think holistically about this approach to circularity, and be aware of it contributing more positively than negatively to the total footprint.

In general, we should aim as high as possible in the hierarchy when developing new products and services.

Repair is not possible if a product is not designed for it. Most consumer technology serve as use cases for this. They are products manufactured for sale and use, and thus impossible to repair. Bicycles are an example of the opposite: close to all parts of the final product can be replaced. The result is a bike potentially kept for life–granted it is cared for and repaired throghout time. If so, the end of your life cycle with this bike can still mean the beginning of another one with a new owner.

Reuse requires a certain quality of the material. Brick, for example, is a very robust and fireproof clay material that can be reused with little retouching from a demolished building facade. Textiles with mixed materials and poor stitching, on the other hand, are unsuitable for neither multiple owners nor particularly many wears.

We are therefore ultimately dependent on designing for circularity.

As a consequence, existing business models, products and services often do not fit into a circular value chain. We are indeed in a demanding and somewhat complicated transition.

All Roads Lead to Cooperation

Judging from our experience, circular business is difficult. No matter if you start off as a linear company wanting to go circular, or as a start-up company in an overall linear economy.

Parkdressen, the company we have founded in partnership with Henrik Hojem, rents out overalls to children of kindergarten age. Both product and the business model are designed for reuse. When the overall is exhausted, after being used by several families, the material is recycled, only to convert to a raw material used in another product.

For the textile industry, Parkdressen's model means a lower carbon footprint. For the families, Parkdressen means saving money on not needing to buy a new overall every time it wears out, or more often: the child sizes up.

Admittedly, the company spends up to three times as much on materials and textiles per overalls compared to the largest commercial overall providers. High quality demands a (fair) price. A known challenge in circular business models. But, in return, Parkdressen's product can be used for at least three seasons by three different families, rather than the typically one from a linear manufacturer.

På(fyll), the company we have founded in partnership with Bakken & Bæck and Orkla, offers refills of household products in standardized containers. These are delivered to your door, and then returned for refilling again from the same doorstep.

The recycled plastic containers can be used at least ten times before needing to be recycled at the manufacturer. På(fyll) thus closes the value chain of the packaging for this type of consumer goods.

Not without challenges either. Most people cannot be expected to understand the benefits of using På(fyll) versus the familiar and disposable alternative.

The solution lies in making På(fyll) a service and experience just as easy, if not easier, than buying a new soap dispenser or refill products at the grocery store. The climate effect of this choice has the potential to result in as much as a 65-80% footprint reduction, according to an LCA report conducted by NORSUS.

Although the entry cost of circular business models such as Parkdressen and På(fyll) appear high, the return is demonstrably greater for both people and the environment, and therefore also the companies.

Still, circularity is undoubtedly difficult to achieve in an already linear business model. Circularity's success rests on realistic expectations and objectives for how one’s industry, service or product and chosen business model can become circular.

Can what we work with, or want to work with, be recycled, redesigned, repaired, or reused? Or better yet, is there anything to reduce?

Perhaps a bit of everything, in creating the potion for a minimal footprint, and a maximally resistant circle.

Photos created using MidJourney

Authors